As the Syrian conflict rages on, discussion in the rest of the world often turns to the question of Syria’s future, and what might be the best way to ensure that a new political system provides the country’s people with their rights as human beings. Necessarily, a large part of this concerns the rights of women and girls to live as equal citizens alongside their male compatriots, and no doubt many regional and international actors will have opinions on how this should be achieved. Here in the West, there is a growing number of voices arguing that, given the rise of ISIS and other extremist groups within Syria, we have little choice but to accept the ongoing dominance of the Assad regime; this position is fundamentally flawed, for many reasons. From a feminist point of view, ISIS extremists are clearly repellent in their treatment of women, but this doesn’t mean that we should see the current regime as a preferable option. Here are some key reasons why feminists should support the Syrian revolution, and not the government of Bashar al Assad:

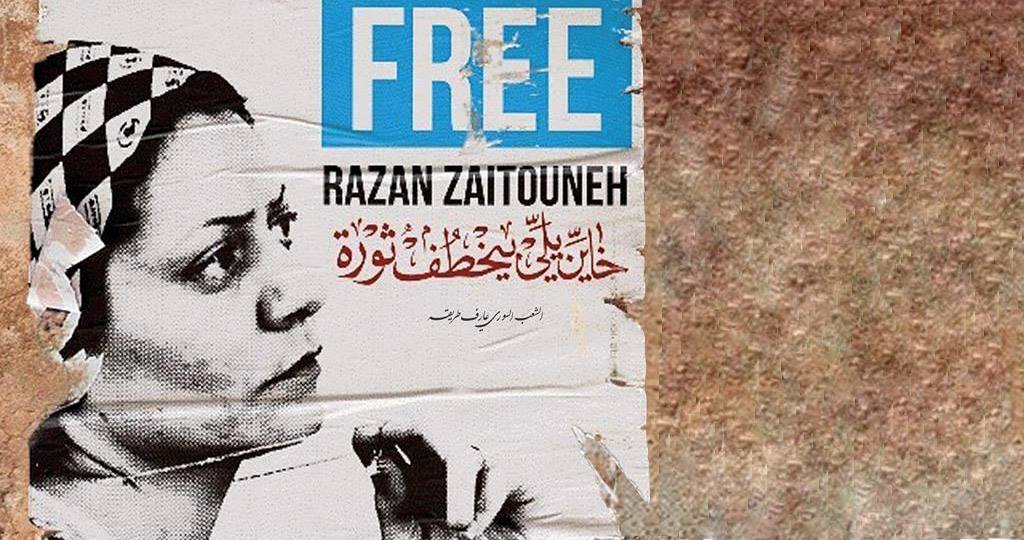

- Syrian women have been key in resisting the Assad regime. Long before the region-wide uprisings known as the “Arab Spring”, Syrians were calling for reform and improvements to civil and political rights in their country, and women played an active part in this. Professional women such as Razan Zeitouneh used their knowledge and experience to lobby the regime to improve the rights of all Syrians. However, the 2011 protests represented the first time that Syrian women from all backgrounds began expressing their political views. They attended and helped organise protests alongside men from their cities; they formed part of the Local Coordination Committees which flourished across the country during 2011 and 2012. While the Syrian uprising was not an avowedly feminist movement, its core principles of freedom and social justice saw a great social shift towards gender equality. What limited women’s participation in the uprising was the way the regime made it into a military conflict. By using armed force and eventually full-scale bombardment against protestors, the Assad regime forced women off the streets and into their homes, while their husbands and brothers took up arms in self-defence.

Source: http://www.abc.net.au

- Assad’s political repression and coercion has not been limited to men. For more than two decades, all Syrians, men and women, have been treated like animals by their government, with no political freedom and very little autonomy. If anyone expressed a negative view about the regime or its leaders, they were very likely to be captured by the intelligence services and tortured. Their relatives also faced repercussions, including kidnap and torture. Women were not immune from any of this; mothers raised their children to feign love for the Assad government, knowing the dangers inherent in independent thought. We need to stop thinking of women as separate from the societies in which they live – the struggle of the Syrian people is the struggle of Syrian women and men to live with dignity.

Source: http://www.adoptrevolution.org

- Regime troops have used rape as a weapon of war. Among the many brutal practices of government soldiers and police officers in Syria has been the public rape of women and girls as a means of humiliating their male relatives. This blatant exploitation of Syrian cultural norms, in which a woman’s honour is seen as intrinsically linked to that of her family, shows that the Assad regime has no respect for women. It sees them as no more than worthless bodies through which they can attack communities which contest its rule.

- The Assad regime enshrined discrimination against women in law. Having long cultivated the image of a progressive, secularist regime, the Assad government has sometimes been lauded as an exemplar for women’s rights in the Middle East North Africa region. Presumably this idea was developed by comparing Syria under Assad to the worst excesses of Saudi Arabian misogyny. While women in Syria have had basic rights such as the freedom to travel without the permission of a husband or father, the law practiced in the country in 2011 actively protected the perpetrators of violence against women from prosecution. Neither marital rape nor domestic violence were prohibited, and “family honour” was considered a valid defence for the murder of a female relative. The minimum age at which girls could be married was 13, and women held a weaker position than their husbands when filing for divorce. With all this in mind, it is very hard to argue that the Assad government has taken any interest in women’s rights beyond “window-dressing” to please the international community. Those women who succeeded in various professions under Assad can be seen as having done so despite significant social and legal disadvantages perpetuated by the state.

Source: http://www.dailycal.org

- Pre-revolution moves to ban the niqab did not represent a concern for women’s rights. The Assad regime’s attempts to portray itself as modern and secular were reflected in a move in 2010 to ban Muslim women from wearing the niqab or full face veil in educational establishments. Here in Europe, we have a weird relationship with the idea of veiling; it’s seen as the ultimate sign of oppression, with discussion of women’s rights in Muslim-majority countries and communities rarely moving beyond the question of whether certain forms of dress should be discouraged. Look, I personally don’t believe that God wants me to cover my face in public, but some women do, and I don’t see why any government should have the right to stop them. A state that tries to tell us what we should do with our bodies, whether its covering them or exposing them, does not have women’s interests at heart.

So there you have it. If you identify as a feminist, don’t fall into the trap of thinking the Assad regime is better for women than ISIS. The only way they can attain true freedom and equality is through the popular, pro-democratic revolution.

Featured image by Rawan Issa